|

While you consider submitting to CLOCKHOUSE Volume Nine, here's something to read from Volume Five. Submissions are open until December 15, and the guidelines and submissions upload button are on the website.

from Helene Barker Kiser’s poem, Bathsheba, to Her First Child: The moment I tilted my face to the sun, hot, even sinking, I felt the king. Or rather, felt eyes sharp as a crow’s. Heat like touch, like a wall of film around me, a substance, heat of his hands but not his hands . My body a fever-- blood-red bloom of a cactus-- the bath water evaporated, surprised by the burn. Strangely calmed by the attention, I loved the early evening, the beginnings of shadows. The sun, I thought it the sun still, unrelenting. I didn’t know there were men around, the war raging on. I didn’t know there was something the king had to do.

2 Comments

The CLOCKHOUSE Volume Nine submissions period is now open! To see guidelines and to submit, just click on "Submit" in the top menu. And for your reading pleasure while you're considering submitting, here's an excerpt from Volume Four: from Lucas de Lima’s poem, because: while they gallop their horses to death

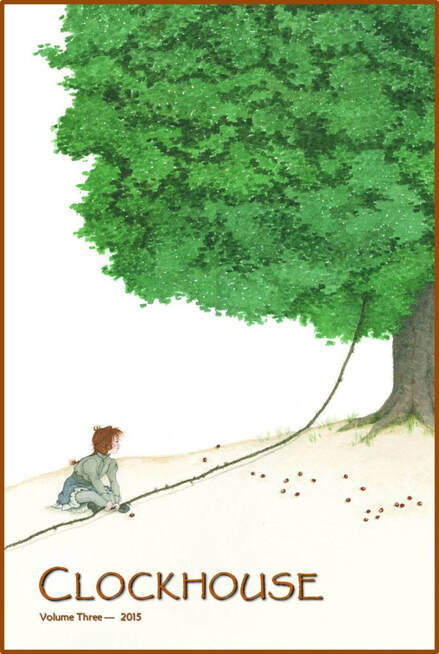

the men’s eyes get bigger the swelling of the roots that upheld the sky merging me & pinto, rainbow & cloud the crisscrossing of myths in a scream so loud it wakens the razorbacks a ripple across the herd every cowboy unhorsed by the roaming of continental horses 8,000-10,000 years ago the unseeing no longer allowed when the arc of our chicken bodie s emboldens the point where sky meets earth where me & pinto wash our feathers we don’t know what we’re preparing for but the infinite seeding of our constellation in the horizon this place & unplace a point already red & black where me & pinto wash our feathers we don’t know what we’re preparing for but the hurling of a rock thru our bodies our thrashing & singing on every scale The CLOCKHOUSE Volume Nine submissions period opens on August 15. In the meantime, here's an excerpt from Volume Three:

from Jennifer Pullen’s Little Red Riding Hood(s), a work of fiction: I Little Red Riding Hood isn’t really named Little Red Riding Hood, her name is Elizabeth, or Mary, or some other good English name. Regardless of whether her name is Mary or Elizabeth she always loves the smell of her mother’s baking, the way she can wake up as dawn wipes gray out of the sky, and even though she has to go milk the cows, gather eggs and pull water from the well, she’s happy. She’s happy because the smell of bread fills her nostrils and makes her feel loved and cared for. Everyone acknowledges her mother as the best baker in the village. Everyday her mother sends her down the path to the edge of the forest to her grandmother’s cottage with a loaf of bread in a basket, because her mother says that a daughter’s duty (she looks pointedly at Mary/Elizabeth as she says this) is to take care of an aging mother. So, Mary/Elizabeth walks down the path every day and brings a loaf of bread. But one day she gets a riding hood of bright scarlet from the church charity bin, and the story starts to swallow her name. If you watch carefully you might be able to see the story lurking in the dusty corners of that church waiting to envelop her. The hood is red and soft and warm and looks like nothing her family could ever afford. Red dye is expensive, red dye belongs to the rich, red dye screams for attention. A grown woman might have one red kirtle for feast days, but only a rich person would make a red riding hood for a little girl. But Mary/Elizabeth gets the hood and then wears it on the walk to her grandmother’s. Wolves can’t see the color red (lacking the appropriate cones to do so), but that doesn’t stop the wolf from seeing the girl and smelling her blood in her veins—hot-alive, and also red. That doesn’t stop the story from going on, doesn’t stop Mary/Elizabeth from getting eaten, it doesn’t save her grandmother, and it doesn’t stop that beautiful bread from going to waste because the wolf is sated on so much red bloody-person-meat. Sometimes a woodcutter saves them, cutting open the wolf, and the grandmother and the girl emerge, probably covered in nasty smelling stomach acid, and hug the wood cutter and everything turns out okay. Sometimes they both get eaten. Sometimes just Mary/Elizabeth. Sometimes the wolf is clever, sometimes the wolf is stupid. But always Mary/Elizabeth ends up as Little Red Riding Hood and always a wolf eats someone. The versions where no one gets eaten aren’t real, and everyone knows it. The CLOCKHOUSE Volume Nine submissions period will open on August 15. In the meantime, here's an excerpt from Volume Two:

from Nancy Kricorian’s poem, Letter to Palestine (with Armenian proverbs): In a foreign place, the exile has no face. You wake up in the morning and forget where you are. The smell of coffee from the kitchen. The sound of slippers across the linoleum floor. It could be any country. When you look in the mirror you see the eyes of your grandfather. He expects something from you, but he won’t tell you what. |

CLOCKHOUSE

A national literary journal published by the Archives

July 2023

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed